Baseball: First Black Player | Its Not Who You Think

/Baseball: First Black Player - Moses Fleetwood Walker Breaks the Color Barrier in 1884

I. Introduction - Rediscovering Hidden History

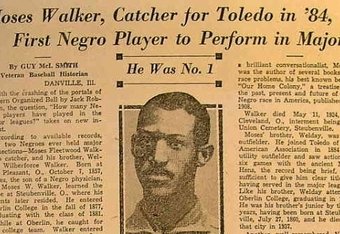

The name ingrained in baseball's civil rights history is Jackie Robinson. His courage in facing discrimination while excelling for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 rightfully earned praise and made him an American icon. However, the full story reaches back over 60 years prior. The actual first African American to integrate the major leagues was Moses Fleetwood Walker - a talented catcher whose brief run ended when racism unjustly exiled him from the sport.

Walker's fleeting opportunity left an obscured legacy compared to Robinson's impact. But re-examining Walker's own stand against hate rewrites baseball's segregationist past. Despite nowhere near the career of Robinson, Walker's place as the pioneering Black major leaguer who first broke through deserves recognition. For if not for the racism that cut short his time in the majors, Walker would be remembered as a trailblazer the same way Robinson is celebrated today.

II. Walker's Standout Skills Draw MLB Attention

Moses Fleetwood Walker possessed all the attributes of a gifted catcher. He had swift reflexes and quick hands to block errant pitches. His strong accurate arm could gun down even the fastest base-stealers. And Walker batted well too - making consistent contact using the whole field.

As a young player, Walker honed his skills competing for Oberlin College where he studied as well. When offered a scholarship to attend the University of Michigan in 1881, Walker jumped at the chance knowing Michigan also boasted a strong baseball program.

The Wolverines at that time featured one of Walker's old teammates in catcher Marcus Hurley. But it only took a few games for Michigan's manager to recognize that Walker outshone Hurley as a backstop. By Walker's sophomore 1882 season, he took ownership of catching duties for the entire schedule - even in the team's tightest games.

That year, Walker allowed just 14 stolen bases while collecting 45 assists throwing out 13 different runners. In an early April nail-biter against the Flyaways club where Michigan clung to a slim 3-1 lead, Walker famously gunned down 3 runners attempting steals in the same inning!

Word of Walker's exceptional talent rapidly circulated at the highest levels. Several big league teams of the era needed an impact catcher. And they saw in Walker a skilled, athletic star in the making perfectly capable of playing among professional athletes. It seemed only a matter of time before Walker drew a contract offer.

Related Terms: Play professional baseball, major league team, martin luther king jr, york Yankees, National Baseball Hall, new york yankees, minor leagues, jackie robinson award, kansas city, african americans, cleveland indians, negro league teams,

III. Chance to Make History - Walker Inks MLB Contract with Toledo

In 1883, the American Association (AA) admitted a new franchise into their major league ranks - the Toledo Blue Stockings. Looking to make a splash, Toledo moved decisively to find an elite catcher who could anchor a roster of talented prospects. Impressed scouts convinced team leadership that they found their backstop in Walker.

By May, Toledo signed Walker off the Michigan squad to a professional contract - making him the first African American player inked by a big league team since the late 1800s. For Walker, joining Toledo meant realizing a bold dream. He would notch a historic first if he took the field as American sport's earliest Black competitor in some 60 years. Certainly, though, the gravity of that responsibility was not lost amid the excitement of Walker's new opportunity.

The Blue Stockings understood Walker would meet hostility as baseball's color line crusher and did well preparing him. Before Toledo's league opener, they scheduled exhibition matches in April and May aimed to ready Walker for the speed and pressure of top-tier play.

Facing tough regional semi-pro clubs, Walker impressed mightily. In Toledo's second contest, he smashed out 6 hits over 10 at-bats including a triple against Adrian High School's pitcher. Walker scored 4 times himself while using his cannon arm to help silence opponent bats. Toledo won 12-6, confirming Walker's readiness to make the jump. Come opening day, he would officially shatter the sport's restrictive barriers.

IV. Walker Excelling Early Against Tough Odds in 1884 Debut Season

On May 1st, 1884, Walker stepped onto the field against the Louisville Eclipse and into the history books batting second in Toledo's opener. He singled in his first plate appearance off future Hall of Fame hurler Tony Mullane. Toledo cruised to a decisive 14-7 win, supported by Walker's 1 for 4 outing.

Just appearing in box scores and holding his own made Walker a target of racist attacks though. Hate mail flooded into Toledo wishing injury or death upon Walker. On the road, Walker was denied hotel rooms and food service solely due to his skin color - instead left to sleep on benches or dine from street carts.

During a series in Kentucky, Louisville players demanded Walker be barred from competing altogether, threatening to strike if games counted with his presence. Acts intended to demean Walker's humanity revealed the uphill battle he waged to simply play on even terms.

Amazingly, Toledo ownership defended Walker, refusing player ultimatums against their rookie. They recognized Walker as instrumental in the club's early success. After finishing the May schedule, Toledo sat third in the American Association standings, exceeding expectations. Walker himself batted .305 over his first dozen games, providing key hits that backed up his steadiness on defense.

By July 19th, Toledo climbed to second place, trailing only the dominant Cincinnati Red Stockings largely thanks to Walker's contributions as an everyday catcher boasting a .284 average. Locking down the center of the diamond, Walker gave Toledo's lineup potency. But off-field animosity persisted, wearing on management.

V. Suspect Release Hints At True Motive by Toledo

Then late in July, Walker badly injured his throwing shoulder, limiting his usefulness behind the plate. Rather than place their starting catcher on injured reserve though, Toledo simply released Walker - cutting ties amid his physical compromise.

The abrupt move after Walker battled through months of racism hinted the organization's sympathy lay not with their player, but his harassers. Perhaps Toledo hoped severing ties would improve business by appeasing those who refused integration.

Sadly, the team took no stand in support of Walker. They made no good-faith effort to assess his recovery. Toledo sacrificed both trust and their catcher who did nothing except excel at playing and endure abhorrent hatred. With Walker gone, Toledo unsurprisingly faded, his solid production impossible to truly replace.

By dismissing Walker, baseball also undid an important early effort to transform its racist culture. Just a few years later in 1889, team owners instituted a despicable “gentlemen's agreement” fully banning Black signings across the entire league. Walker's exile helped baseball cement harsher discrimination policies for decades to come.

VI. Rise of Negro Leagues Provide Opportunities Amid Segregation

With Moses Fleetwood Walker exiled from Major League Baseball - along with all other players of color - talented African American athletes were forced to carve their opportunities outside American society's mainstream. Independent Negro baseball teams started sprouting up everywhere providing chances for Black professionals long denied avenues because of racism.

Competitive leagues fully developed by the early 20th century as rosters featured numerous stars. Pitchers like bullet-throwing Satchel Paige, crafty submarine specialist Phil Cockrell, and fireballing Smokey Joe Williams dominated hitters with expansive skillsets. Towering slugger Josh Gibson became known as the "Black Babe Ruth" for prolific home run power that regularly bested MLB benchmarks. Cool Papa Bell's blazing speed covered outfield gaps in the blink of an eye while also swiping over 175 bases in single seasons at opportune times.

Together, the Negro Leagues nurtured proud generational talent despite segregation. Owners organized barnstorming tours so skilled African American clubs could entertain Black communities nationwide. However, many felt anger at being denied chances in MLB solely over race. Having separate leagues that Whites considered inferior could never reflect true equality in America.

VII. Robinson Revolutionizes Baseball and Society in One Move

When Brooklyn Dodgers executive Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to an MLB contract before the 1947 season, he set a sweeping social transformation in motion. Rickey knew Robinson faced an uphill fight, but believed Jackie had the talent and temperament to excel through racist adversity. And by re-integrating baseball's highest level, Rickey saw a way to revolutionize the sport's restrictive cultural landscape on a national scale.

Early on, the level of racial abuse toward Robinson was staggering. Some Dodger players circulated a refusal to play alongside him. Opposing pitchers aimed fastballs at his head and players spiked his ankles with malicious intent. Even fans at Ebbetts Field heckled Robinson using unthinkable slurs when he took the field for home games.

But Robinson kept his composure, letting undeniable hitting skills silence critics. He earned Rookie of the Year honors in 1947 batting .297 while igniting pennant-winning rallies that year and many to follow. When Robinson took the field, America took notice. And though early on not all came to praise him, his courage through fire helped turn the cultural tide of both baseball and broader society.

While the American League remained all White as late as 1953, National League owners followed Rickey's charge signing more Black stars after Robinson found success. Within years, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Ernie Banks transformed the game blending remarkable talents across skin colors. The integration of baseball profoundly shaped America's institutes well beyond sports.

VIII. Walker's Legacy Deserves Recognition Despite Brief Run

While Jackie Robinson justifiably looms large in advancing civil rights through his hallmark MLB career, Moses Fleetwood Walker's fundamental contributions remain obscure. He does not have a career to celebrate like Robinson, OwnerId Ty Cobb. Aaron broke barriers playing a game he loved for 23 illustrious years amassing one of the sport’s most prestigious records. Meanwhile, Walker competed just a single season in Toledo before unjust forces cut short his run.

And yet Walker undeniably achieved a tangible first some 60 years prior - competing on level terms as a colored catcher in the major leagues when no African American had done so since the Reconstruction Era. That pioneering step alone deserves the honor by baseball historians even if opportunities after went unfulfilled.

Consider that by the numbers, Walker was well on his way to stable production for Toledo. Over 42 games in 1884, he batted .263 with 2 triples, 5 doubles, 19 runs scored, and also boasted a sturdy .979 fielding percentage behind the plate. Project those figures over a full season and Walker likely develops into an eventual all-star performer.

There are certainly cases arguing for Walker's place in Cooperstown given such projections and his significant early contributions. At minimum, blackball committees should commemorate Walker annually for the vision and mental resolve to pursue his dream knowing hate awaited. What he symbolized in staring down racism's ugliness merits baseball's highest recognition.

IX. Shared Inner Fortitude Against Intolerance

Considering baseball's uncomfortable past regarding civil rights, both Jackie Robinson and Moses Fleetwood Walker displayed enormous inner strength and grace when confronted by racist harassment from all sides. America's history is riddled with people of authority and institutions leveraging that power to exclude, demean, and brutalize minority groups.

Walker and Robinson alike shouldered their duty - not strictly personal but inherited from generations of suppression - to walk upright with dignified hope toward freedom through America's favorite pastime. In their quest to achieve measured justice, both men awakened the conscience of their opposition through pure demonstration of skill and character.

Robinson persevered longer on baseball's biggest stage, overcoming with superior production and more visible activism against injustice. But that should not discredit Walker's heart and courage in first crossing cultural fire 60 years prior. Their symmetry of vision pierces to moral truth about equal access and opportunity for all athletes in a just world. Baseball owes a great debt to both men for exposing its unfairness while also transforming the sport for the better.

Conclusion - Two Sides of the Same Civil Rights Coin

In revisiting baseball's history with racial intolerance, Moses Fleetwood Walker emerges as an overlooked figure foundational to the integration narrative. He proved Blacks could compete long before Jackie Robinson's heralded arrival. Unfortunately, Walker never got the full opportunity to display his talents. When considering what he still achieved through pure mental resolve in a singular season, Walker earned a place right alongside Robinson as a true pioneer against discrimination.

While Robinson made the bigger social impact thanks to a long successful Dodgers career soon opening doors, the risks and sacrifices Walker made as baseball's first known Black major leaguer cannot be understated. Their journeys share poignant similarities in significance. Without Walker's courage stepping into uncertain terrain years ahead of his time, perhaps the seeds of progress later culminating in Robinson's breakthrough never taken firm root.

In the end, both men moved equality forward. They emerged from hate stronger by not allowing harassment to breed self-doubt in their rightful place among top-tier athletes. Baseball owes deep thanks to Jackie Robinson and Moses Fleetwood Walker as heroes central to the game's complex civil rights history.